Cultural Shock 101: The Invisible Class System of Latin America

And Where Foreigners Adapt, Fit, and possible Thrive

This is a hypothetical essay. It’s my opinion based on observation, conversations, and pattern recognition. I’m not claiming this is “proven,” or that it applies equally everywhere, or that every person participates in it consciously. If you disagree, that’s not only allowed, it’s the point. This is an attempt to name something that a lot of foreigners feel but can’t describe.

When people move to Latin America, especially if they’re coming from the U.S., Canada, or parts of Europe, they usually arrive with a sort of mental relief. They think they’re stepping out of the Western race conversation.

The American version of it feels exhausting, moralized, and permanently online, so the idea of landing somewhere “warmer,” “simpler,” and “more mixed” feels clean. There’s a common myth foreigners tell themselves: everyone here is mestizo, the country is mixed, so the harsh lines don’t exist. People might be poor, sure, but that’s economics. Racism, in the American sense, doesn’t arise neatly, so maybe it isn’t the central organizing force.

And for a while, that story seems true, mostly because the first phase of expat life is a honeymoon where you are treated as an outsider. You get curiosity points. You could also call it the “tourist glow,” even if you’re not a tourist. People ask where you’re from, they listen to your accent, they laugh at your mistakes, they invite you places.

That’s why so many foreigners mistake friendliness for equality.

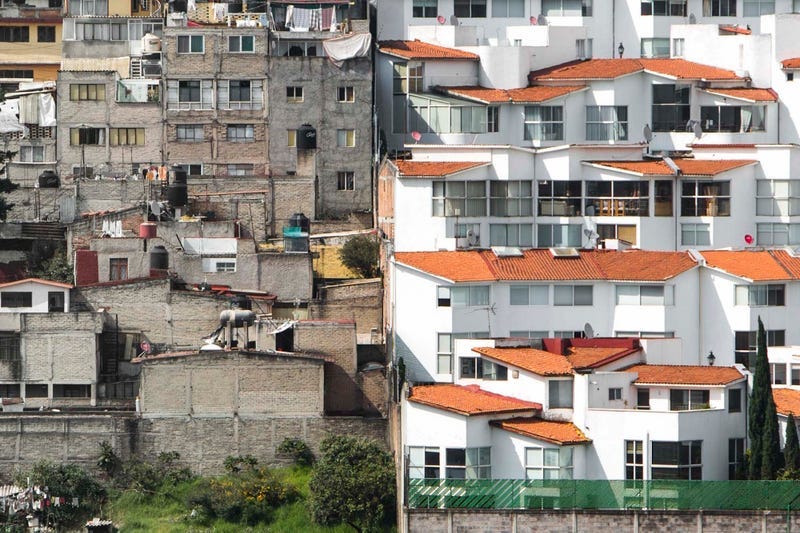

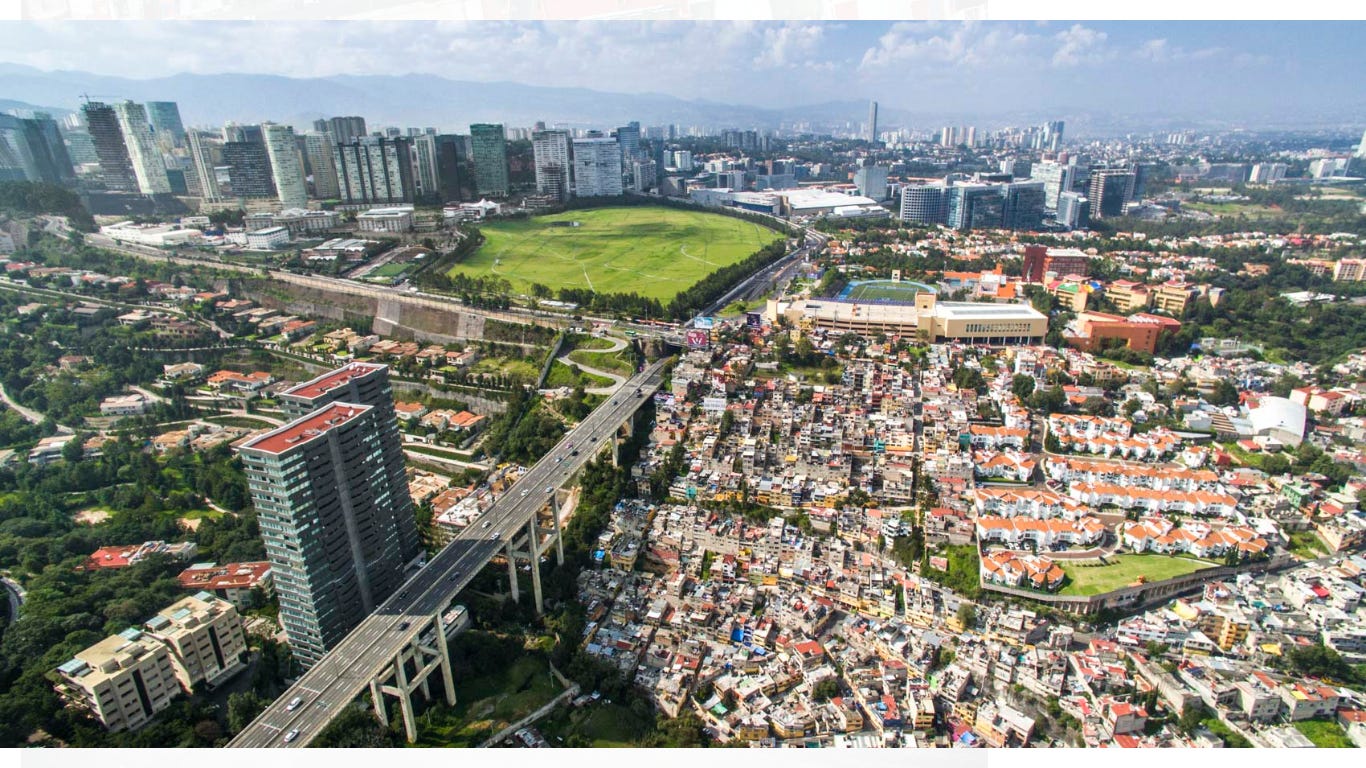

Eventually, you know notice differencee with how the locals treat each other. It’s subtle enough that you can typically ignore it. You’ll notice that some people move through the city like it was built for them, and others move through it like they’re borrowing space. You’ll see how certain first and last names make differences before money does. You can see how “class” doesn’t equal income. Instead class is a posture, a tone, a type of Spanish, a type of face, a type of neighborhood, a type of school, a type of family story.

Latin America doesn’t need ideology to maintain hierarchy.

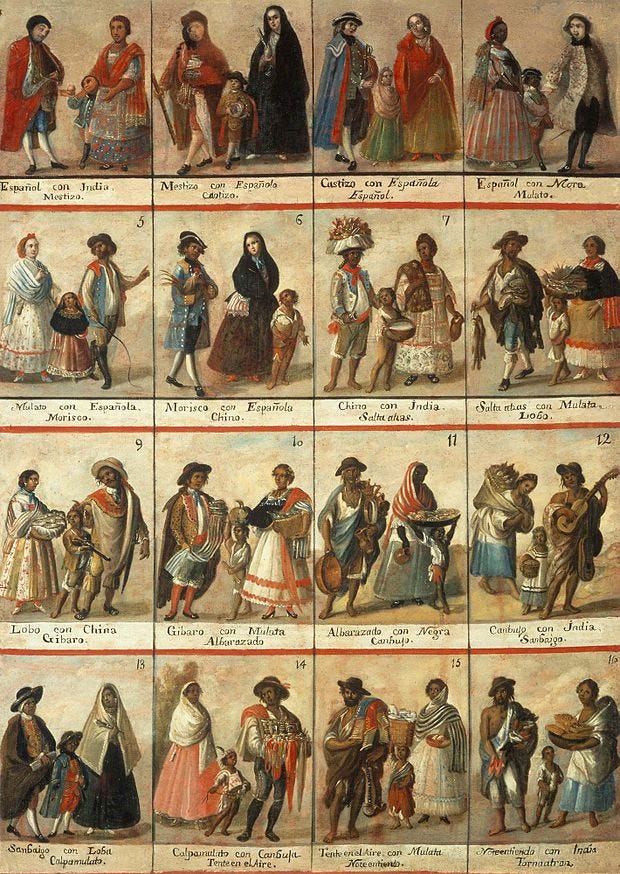

Here’s my hypothesis: The region never escaped its colonial class system, it just stopped calling it that. The formal categories were abolished, the legal caste charts were buried, and the national myth shifted toward unity and mestizaje, but the preferences and mental shortcuts of the locals still exist and became polite. I believe foreigners don’t see this as often because because they often interact with multiple classes of people during their day, and those people also know that you don’t understand their class system so it gives them a place to pretend it doesn’t exist.

But Latin America is also often allergic to frank statements said out loud. It prefers implication where social heirachy can be enforced, but not spoken of.

The colonial period is what comes into place here. I am not a history lecture, but because colonialism mixed the populations, it also organized them. The Spanish and Portuguese empires weren’t only extracting resources; they were building a social order where lineage, phenotype, and proximity to European identity correlated with legal rights and social legitimacy. They didn’t expect their colonies to eventually gain independence.

The categories:

peninsular, criollo, mestizo, mulato, indígena, negro, determined who could be treated as “respectable.” After independence, rthe hierarchy seeped into the culture.

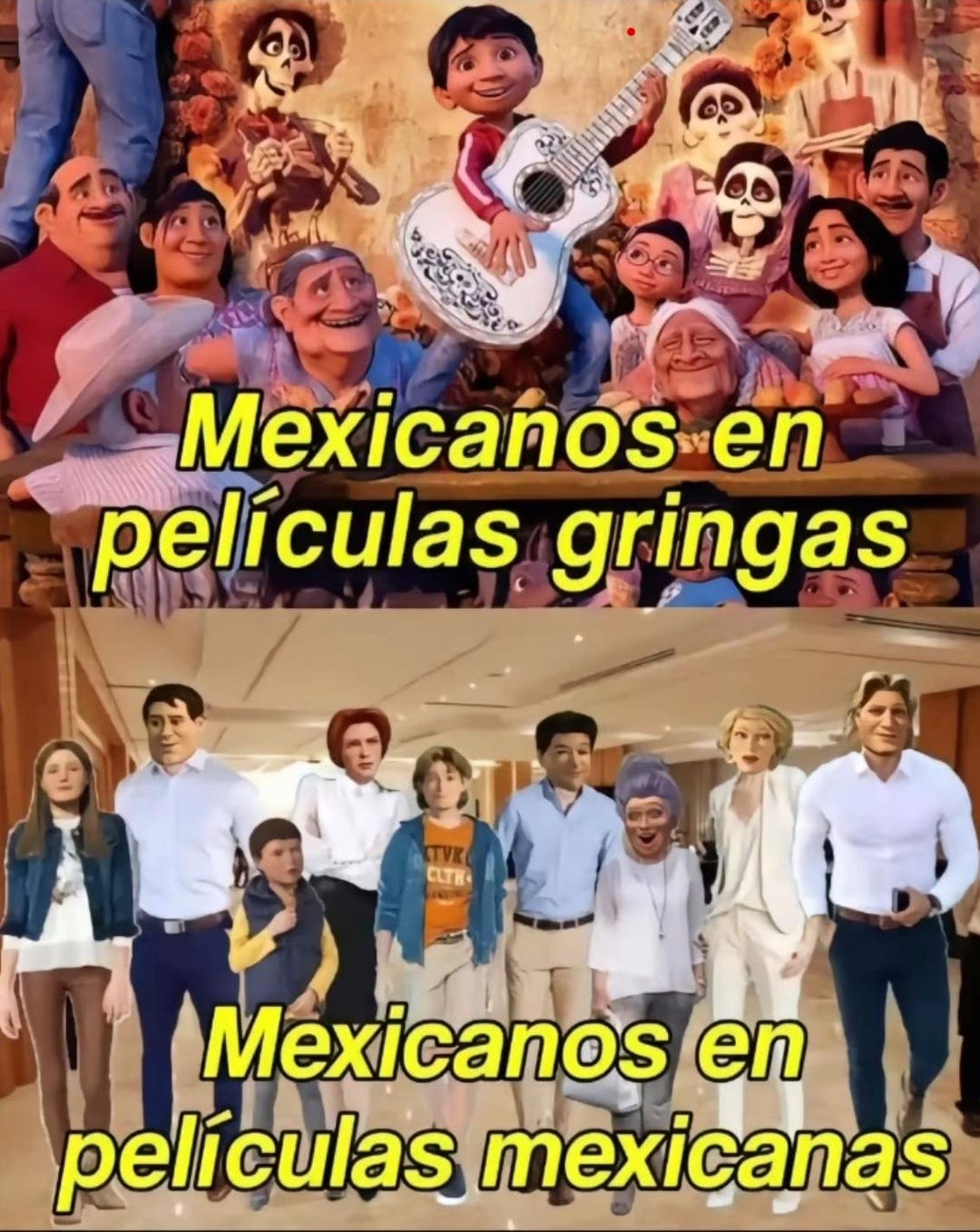

Another reasons this is so confusing for foreigners is that Latin America is genuinely mixed and creates plausible deniability. In societies where people come in a wide range of shades and features, it becomes easy to claim, honestly, that “we’re all mixed,” and therefore racism is not the issue. .

I see it in the compliments and casual language. If you spend time in Mexico, you’ll hear “güero” function like a social upgrade. Whereas calling someone “moreno” can be used to poke at someone. Some people are “taking back” the term indio and prieto, but historically its been used more derogatory.

At the same time, the people who deny colorism most aggressively are often the ones who benefit.

The next layer is class, but not class as foreigners usually define it. In America, class tends to be talked about as income, education, and occupation. In Latin America, it’s often family origin. Not purely as if your parents were rich, but whether your family belongs to a known network, whether your surname rings a bell, whether your lineage fits the aesthetic and cultural template of “good family.”

That’s why expats will sometimes witness a paradox that confuses them: someone who is objectively well off is still treated as “not quite one of us,” You can see this easily in more well off areas like polanco, Where even amongst “Fresas” there’s a class system of style, and how long your family has been well off.

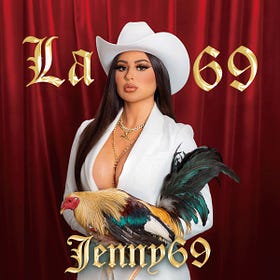

Mexican Subculture - The Fresa

Expanding on my previous article on Buchonas, let’s continue on to Fresas.

And to be frank, phenotype is often as a shortcut for who is who. This is not to say lighter mexicans are rich or darker ones poor. It’s just that the the aesthetic profile of the elite tends to skew lighter, and the aesthetic profile of the working class tends to skew darker. People often try to dress themselves in a way to signal high class in a way which Americans have slowly moved away from.

Local media also reinforces this. Telenovelas, advertising, fashion, politics are usualy presented with a consistent preference for European features. Sure, this is not uniquely a Latin American thing, but the contradiction produces a strange psychological effect. Foreign Media usually present as the the average population.

It lets local society enforce an aesthetic hierarchy while publicly denying that it’s doing so. If you call it out it, you become the annoying foreigner importing “American identity politics,”.

Mexican Subcultures - The Buchona

The term "Buchona" came out of the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where it was used to describe the flashy, flamboyant girlfriends of a new breed of narco. These guys were known as "buchón" or "buchones" - real macho types…

But Why call this “cultural shock”? Foreigners often think they’re entering a more relaxed and equal social environment, sometimes discover that a lot of opportunityespecially in dating, business, ect. You can brute force their way through with “merit” and “directness,” because foreigners live outside the system. But some linits exist.

Many can live for years and never notice this if they stay inside an expat bubble or inside a tourist lifestyle. But once you start trying to integrate deeper, you may eventually run into it. Not always towards you, but how you integrate the friend groups you inevitably have.

But how do you overcome this…

**Please don’t forget to like the article to boost it in the Substack algorithm

If my hypothesis is even partially true, then the question becomes practical: how do you move through a society where the class system is quiet, aesthetic, and relational? Foreigners can actually do well in these environments, sometimes better than locals, but only if they stop assuming the rules are the same as back home.

The first advantage foreigners have is that you are initially “categoryless.” Locals can’t immediately place you into the domestic hierarchy. You’re foreign, which means you’re both valuable and suspicious. Valuable because you represent novelty, global connection, possible money, possible status.

Suspicious because they know you might not understand the social codes, but you might eventually learn the signals.

One signal..is restraint.

Latin American upper class seem to tend to signal status through understatements. Over explaining is on tell. They introduce themselves with long descriptions of status so you know where they stand in society. To foreigners, this might seem odd because outside of freshly graduated people, no one really leads with they degrees and titles. When people do flex their titles, it comes of as trying to hard.

Over dressing is another tell. People here tend to dress in posh fashion if from that class, everyone else typically dresses up, whereas Americans have started to dress down. American upper class dress as regular as possible, or if wealthy ( quiet wealth), whereas latin america wants you to know who they are. This is why materialistic capitalism is booming here.

Over flexing as I would call it, is the third tell. Loudness, especially American loudness, reads as insecurity. A foreigner believes competence is often communicated indirectly: through calmness and through etiquette. The latin needs to express to you from the beginning who they are and why they are important.

The last is endorsement. In many places, relationships precede transactions. Some say this is inefficiency, other says It’s part of the economy trust. Institutions here are weaker; corruption is more normalized. People rely on networks. You need someone to vouch for you. This is why there are so many “fixers” throughout Latin America.

Foreigners who try to “network” like Americans, collecting contacts and pitching fast, often come off as predatory. Foreigners who move slower, build rapport, and let others bring them in tend to win. It seems slow, because it is, but thats the system.

Then there’s language. Most foreigners assume the goal is fluency. Fluency helps, but what matters more is what your Spanish signals. Spanish is a class performance. Accent, cadence, vocabulary, and even jokes signal what kind of person you are.

In some contexts, speaking too casually or using the wrong slang can lower your perceived status. In other contexts, speaking too formally can make you sound cold or arrogant.

I specifically highered Marcelo, to get me up to speed in this department. I didn’t want to learn from someone posting a poster in a park for 5 dollars and hour and teach me slang, I wanted a “professionally” fluent teacher.

This is similar to anywhere in the world, but often overlooked. If you’re going to speak well, you also have to speak appropriately for the environment you’re in. Otherwise, you become a mismatch: the foreigner who sounds…too local might come not be trusted as much.

Foreigners do have the ability to cross class lines without losing status, whereas A local might be penalized socially for mixing too downward or too upward.. A the same time, being too polished my come of as a “conqueror” type.

Dating can also be teacher of this framework because it exposes the system in a way business can hide. In many Latin American contexts, families still matter. Social circles still matter. Reputation still matters. Foreigners can date across lines more easily at first because “foreign” itself can be a status symbol. But when the relationship turns serious, class might show up through family approval, lifestyle expectations, and social compatibility.

This is also where many foreigners get caught holding the bag and being expect to take care of the whole family because they picked the wrong partner.

Don't Bring Her Back To Your Country

The idea of finding a foreign partner and bringing her back to the West has been a controversial topic for years. My opinion... It's a ridiculous idea that often ends in failure. The girl either leaves and goes back home, or she leaves and falls into the trap/learns the traits that you originally left the West for. Here are some of the nuances and complexities in the situation. Let's start with the cultural adjustments.

You might be good enough for fun but not good enough for marriage. Or you might be accepted because you bring status or stability.

Another question that dances around: Can you leverage this system? The answer is yes, if you define “leverage” as alignment rather than exploitation.

You leverage it by building real trust vs pretending to be someone you’re not. AKA the guy at the resort bar that brags that he’s good with the staff cause he speaks a little spanish. Meanwhile the staff might have no issue fucking him over when the time is right.

I think future is interesting because the old hierarchy is being challenged by new money, remote income, and global mobility. Digital nomads create a new layer: foreigners with money but no lineage. Locals with lineage but less money can resent them. Locals with money but no lineage try to ally with them. The old system is fighting to stay in place.

"Gringo Go Home" is a Psyop by the Latin Elite

The "Gringo Go Home" wave springs up every so often. Like most other liberal movements, I have to assume that someone behind the scenes is funding it. It's likely the wealthy class that wants foreigners to be blamed instead of the local elite. Here is my theory: in the case of Mexico City, the majority of foreigners live in "The Bubble" neighborhoods su…

If you’re an reading this and you’re thinking, “This feels wrong,” cool, ok. This is just my opinion, but my point realism.

If you want to argue with this framework, do it in the comments. Bring counterexamples. Bring your country specific experience. Tell me where it’s wrong. Tell me where it’s right. I’m not attached to being correct…I’m attached to mapping reality.

Social Circle & Cultural Integration Tips

If you're planning to actually live in Mexico…not just hop around as a digital nomad with a laptop and a dream, you’ll need more than tacos and Tinder to feel integrated. “being cool” isn’t enough…most people really aren’t. Latin America runs on connections, community, and culture. If you want to build here… aka friends, business partners, romantic options that aren't transactional, you’ll need to learn how to break into the local scenes unless you’re happy living in a bubble and seeing the same foreigners that pop in an out ever couple months.

The only thing I’m confident about is that foreigners who ignore these dynamics tend to misunderstand their own outcomes, and foreigners who learn them tend to stop being surprised.

And once you stop being surprised, you finally start choosing your moves instead of stumbling into them.

**Please don’t forget to like the article to boost it in the Substack algorithm