The Mestizo Lie: Mexico’s National Face Blindness

How a century of state propaganda turned a nation into a room full of strangers.

Due to high demand, this article is available in both Spanish and English. Please click here for the Spanish version.

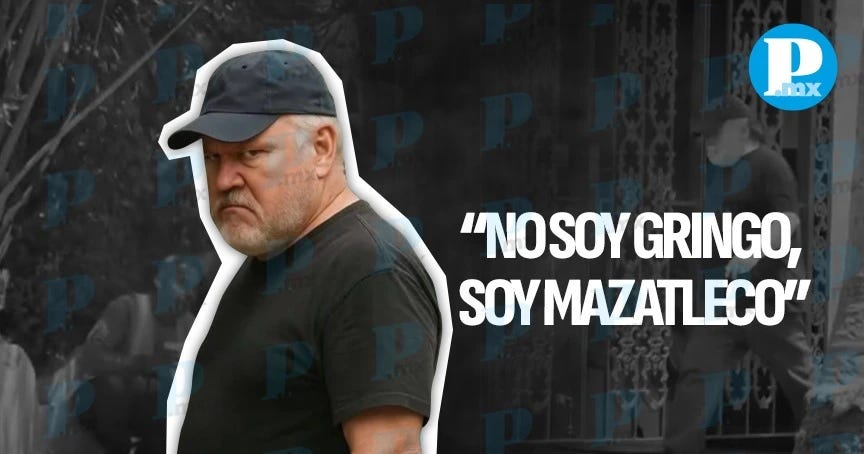

The air in Mazatlán is usually thick with the salty scent of the ocean but in April 2025, it was thick with righteous indignation. Outside a home on Cruz Lizárraga Avenue, a mob had gathered to exorcise a what they thought was a demon… A Gringo. Waving Mexican flags and blasting banda music, the crowd threw eggs and insults at the house of a “Gringo” who had supposedly harassed a local construction worker. To the digital onlookers on TikTok and X, it was a clear-cut case of the local David standing up to the imperialist Goliath.

The problem was…The man inside, José Ignacio Lizárraga Pérez, was not a Gringo. He was a 78-year old retired lawyer whose family had lived in Mazatlán for generations. He was as Mexican as the street he lived on a street, ironically, named after a famous Mexican musician, not his family. But, to the eyes of the mob, his skin, his age, his property, and his posture rendered him an alien.

This was a glitch in the matrix of Mexican identity. It was a demonstration that despite a century of nationalist rhetoric, many Mexicans actually have no idea what a Mexican looks like. While Americans have spent centuries perfecting a “behavioral” nationality that transcends race, Mexico has doubled down on a “phenotypical” myth that is eating itself alive.

This article is a narrative think piece in social observation and educated guesswork. My perspective is shaped identifying patterns and ‘glitches’ in a systems. I am not claiming to be the final word on Mexican sociology; I am pointing out where I see gaps. If you disagree with my assessment, you aren’t just allowed to say so, I’m inviting you to. Disagreement is the fuel for a better conversation.

Please don’t forget to like the article to boost it in the Substack algorithm.

The American Software vs. The Mexican and European Hardware

To understand why Mexico struggles with its own reflection, we must first look at the neighbor to the north. In the United States, identity has evolved into something a “software” that anyone can run regardless of their “hardware.”

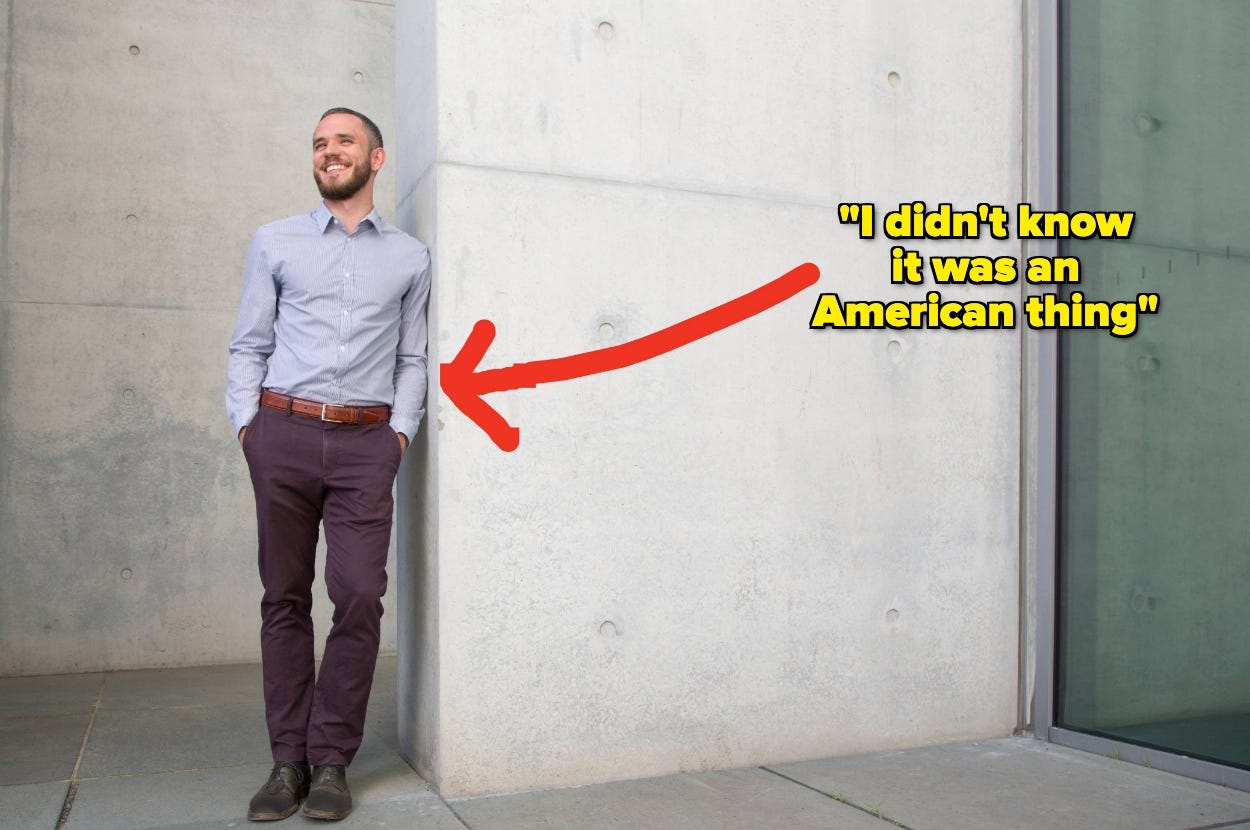

There is a specific, purposeful way that Americans move through the world. It is what sociologists often call the “American Walk.” It is wide-based, heavy-heeled, and linear. An American doesn’t meander or weave through a crowd; they “bull” their way through with a sense of entitlement to the space they occupy. Their steps are big, their arms swing with a certain rhythm, and they command a at least a 3 foot radius of personal space everywhere. This gait is so distinct that in Europe or Latin America, a local can often spot a US citizen from 50 yards away, even if that citizen is ethnically indistinguishable from the local population.

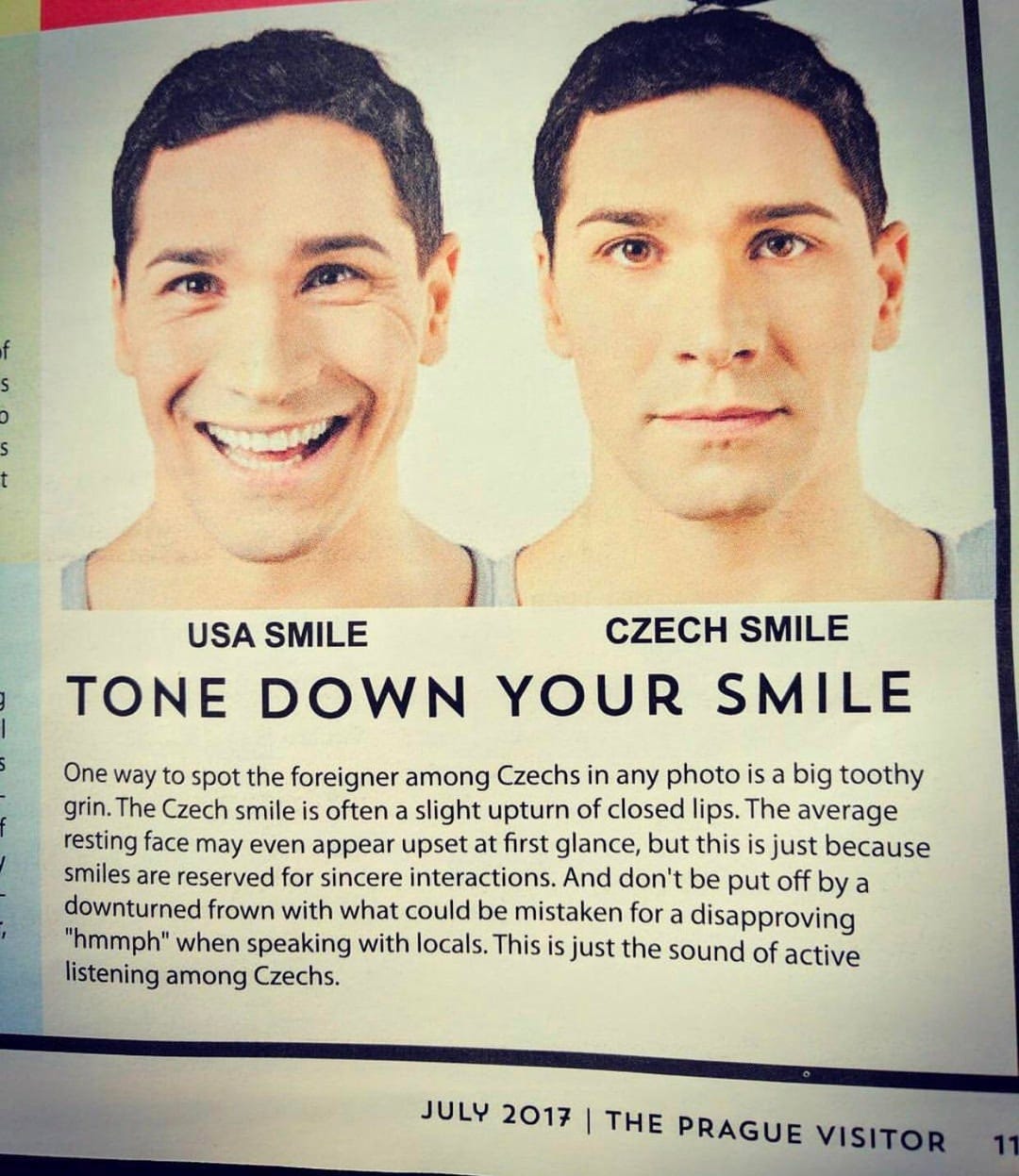

This behavioral barcode extends to the “High-Intensity Smile.” Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have noted that in “high-migration” countries like the US, people from vastly different backgrounds developed “performative faces.” When you cannot rely on shared lineage to signal “I am not an enemy,” you use a wide, toothy, high energy grin to bridge the gap. It is a universal translator of intent for Americans.

Contrast this with the “stoic mask” common in the interior of Mexico or most of Europe. In these “settled” cultures, a smile is an earned currency; it is reserved for moments of genuine happiness. To a Mexican, the American smile looks like a theatrical mask of insincerity and aggression. To an American, the Mexican face looks like a locked door. Because of this, the American identity is portable. A 3rd generation Japanese-American in Los Angeles “looks” American because of how they hold their shoulders and how they project intensity. They are recognizable as “Western” even in Tokyo. In the US, the software is built on a set of morals and ideals. If you run the software, you are the person.

In Mexico, the opposite has happened. Identity is anchored in “Peoplehood” or a shared origin story and a specific “hardware” known as the Mestizo. But because that hardware is a chaotic 500-year-old cocktail of Spanish, Indigenous, African, Filipino, and Arab blood, the “Standard Mexican” doesn’t actually exist. When a nation is told for a century that it is one thing, but its eyes see a thousand different things, it develops a form of national prosopagnosia … face blindness.

A Mental Grid That Won’t Die

I think the root of this confusion is colonial. Long before the Mexican Revolution, the Spanish Crown attempted to map the chaos of human biology through the Sistema de Castas. This wasn’t a simple binary of “Spanish” or “Indian.” It was a dizzying grid of sixteen or more classifications. There were Mestizos (Spanish and Indian), Mulatos (Spanish and Black), Castizos (Spanish and Mestizo), and even the cruelly named Saltapatrás ( “a jump backward”), used when a child appeared more African than their parents.

These Cuadros de Castas (Casta Paintings) were mythical “How-To” guides for the colonial eye. They were meant to tell the viewer exactly what a person was based on the shade of their skin and the texture of their hair. While the legal system of the Casta died with Independence, the mental grid still exist.

Cultural Shock 101: The Invisible Class System of Latin America

This is a hypothetical essay. It’s my opinion based on observation, conversations, and pattern recognition. I’m not claiming this is “proven,” or that it applies equally everywhere, or that every person participates in it consciously. If you disagree, that’s not only allowed, it’s the point. This is an attempt to name something that a lot of foreigners feel but can’t describe.

Mexico today is still plagued by these “versions” of itself. There is the Mexico of the northern Germanic and Mennonite enclaves; the Mexico of the Lebanese and Arab merchant families like the Slims and the Hayeks; the Mexico of the Afro-descendants in Guerrero who were only officially counted in the census for the first time in 2020. According to the 2020 INEGI Census, over 2.5 million Mexicans identify as Afro-Mexican, yet they are frequently stopped by authorities who assume they are from Central America or the Caribbean.

Because the national rhetoric indoctrinated through state issued textbooks—insists these groups have all merged into a single “Bronze Race,” the average person is left without a mental map to navigate the reality of their neighbors. This is the irony of Mexican diversity: everyone is taught that they are the same, yet everyone knows they are different. If the man in Mazatlán doesn’t fit the “Bronze” average, he must be a Gringo. If a family in Chiapas speaks an indigenous tongue but doesn’t look like the “poverty-stricken” archetype, they must be Central American.

The Philosophers War” Vasconcelos vs. Gamio

The failure to recognize the Mexican face is a direct result of two competing philosophies that emerged after the 1910 Revolution: the “Cosmic Race” of José Vasconcelos and the “Indigenismo” of Manuel Gamio. These were not just academic theories…they were state mandated psychological blueprints.

Vasconcelos, the first Secretary of Public Education, gave Mexico its most famous myth: La Raza Cósmica. He argued that the races of the world would eventually merge in Latin America to create a superior race: the Mestizo. On paper, this was a beautiful, anti racist ideal. In practice, it was a tool of erasure where declaring that everyone was “on their way” to becoming the same, Vasconcelos effectively made it un-Mexican to stay different. He didn’t actually celebrate diversity based on his writing. He wanted the dissolution of diversity. If you weren’t “Bronze,” you were a lingering relic of the past or a foreign invader.

On the other side was Manuel Gamio, the father of Mexican anthropology. Gamio’s “Indigenismo” was more grounded but no less manipulative. He believed that the indigenous past was the “true” heart of Mexico, but only if it could be modernized and integrated into the state. He wanted to preserve the aesthetic of the Indian while erasing the autonomy of the Indian. Gamio’s work also fueled the Neo-Marxist movements in Mexico that sought to frame the national identity through the lens of class struggle or the “Pure Indian” as the oppressed and the “White Spaniard/Gringo” as the oppressor.

Between these two giants, the modern Mexican identity was killed. Vasconcelos taught Mexicans to look for a “Cosmic” average that doesn’t exist, while Gamio taught them that “Indianness” was a class marker. This created a psychological disconnect that when a Mexican sees a light skinned person, their brain—trained by textbooks and the “Telenovela Filter” and rarely says “Compatriot.” It says “Hero” or “Wealthy” or “Foreigner.”

The “Aesthetic” of Poverty

This leads us to a secondary, more insidious filter: the belief that “Mexican-ness” is inextricably tied to poverty. In the national psyche, the “true” Mexican, the one Vasconcelos and Gamio romanticized is the humble campesino, the worker, the person struggling against the weight of history. Consequently, any display of ease, wealth, or modern luxury is viewed as an “infection” from the North.

This is best illustrated by the polarizing reception of Yalitza Aparicio, the Mixtec star of the movie Roma. When Aparicio was nominated for an Oscar, the international community celebrated her as the face of Mexico. Yet, within Mexico, she was met with a tidal wave of vitriol.

The hate for Yalitza was a collision of racism and classism. By appearing on the cover of Vogue in Dior, she violated the “aesthetic of poverty” that the Mexican elite uses to keep the indigenous population in a box. In the Mexican mind, if you look like Yalitza, you are “supposed” to be the help. When she ascended to the global elite, she broke the “hardware” expectations of the nation. She was too indigenous to be that successful, and therefore, her success was seen as an affront to the social hierarchy. Success, for an indigenous Mexican, is often viewed as a betrayal of their “true” identity or an identity that the state wants to keep frozen in a museum of the 1920s.

Fátima Bosch: Beauty as National Yet Foreign Capital

On the other end of the spectrum is the case of Fátima Bosch, who won Miss Mexico (Nuestra Belleza México) in the last year. With an Arabic first name and a Germanic last name, her victory initially sparked a firestorm of “internal xenophobia.” Critics argued she didn’t “look Mexican” enough to represent the country. She was, to them, another “Whitexican” bubble inhabitant who had no business representing the “Real Mexico.”

The irony is that as soon as she began to win and bring prestige to the national brand, the narrative shifted. Suddenly, her “unique” look was claimed as a point of pride. This reveals the hollow nature of Mexican nationalism: “Mexican-ness” is a fluid concept that is denied to you if you are inconvenient but granted to you if you are beautiful or successful enough to improve the national image.

Beauty in Mexico is a tool of the state. In the world of pageants and media, beauty often represents a “Global Standard” rather than the “Regional Reality,” yet the population is indoctrinated to accept these winners as the “best” of Mexico, even as they frown upon people on the street for looking exactly like them.

*Please don’t forget to like the article to boost it in the Substack algorithm.

Misinformation as Nationalism

In the pre-Internet era, identity was negotiated in the town square. You knew your neighbor because you saw them every day. But in the 2020s, Mexican nationalism has been outsourced to the TikTok algorithm. The “Digital Lynch Mob” is the new enforcer of the Mestizo Lie.

The Mazatlán incident went viral because a single 15-second clip stripped José Lizárraga of his history. The algorithm doesn’t care about his birth certificate or his deep roots in Sinaloa; it cares about the “vibe” of conflict. By labeling him a “Gringo” in the caption, the uploader activated a latent “Defense of the Fatherland” reflex in millions of viewers.

This is “Face Blindness” as a service. Social media provides a platform where people can perform their nationalism without ever having to engage with the reality of their fellow citizens. It allows a person in Mexico City to feel “patriotic” by attacking a man in Mazatlán they’ve never met, based on a phenotype that doesn’t fit a textbook definition. This digital nationalism is actually destroying real-world communities by turning “different” neighbors into “invading” content.

The Theatricality

Another example of this failure of the “Shared Peoplehood” shows up in the minority populations of the state. In 2015, the Juárez siblings, Amy, Esther, and Albert, were pulled off a bus in Queretaro by agents of the National Institute of Migration (INM). They were Tsotsil Mayans from Chiapas.

But they didn’t “look” Mexican to the agents. They looked like “Central American migrants.” When their ID papers were presented, the agents declared them fake. Even after singing the National Anthem, the family was still under question for 8 days.

The only way the state can recognize its own citizens is to make them perform a song. But because the siblings’ first language was Tsotsil and their Spanish was limited, their performance didn’t “sound” Mexican enough. Alberto was eventually tortured with electric shocks until he signed a “confession” stating he was Guatemalan.

Even activists like Irineo Mújica, a dual citizen who looks “Mexican” by most standards, have been detained and had their identity questioned by authorities.

The Internal Scam and the “Foreigner Tax”

This example of blindness filters down to the most mundane interactions. Take the “Foreigner Tax.” Westerners living in Mexico often complain about being charged more by street vendors, but this isn’t always a matter of simple greed. Often, the vendor literally cannot conceive of the person in front of them being a Mexican.

I have a friend who “looks” Mexican to me, but his “software” is slightly different. He carries himself with a certain confidence; perhaps he dresses in a way that signals “North.” I have seen him get charged “Gringo prices” by indigenous vendors for the same items I’ve bought. At a point he doesn’t even object. He realizes in their eyes and their “internal casta grid” he might not be “Mexican”

In your own barrio, you are a Mexican. Three neighborhoods over, if your skin is a shade lighter or your shoes are a bit too clean, you are a target.

The Pocho and the Chicano: The Strangers

Finally, I account for the 35 million people who fall into a crack in the mirror: the Pochos and Chicanos. When these Mexican-Americans return to Mexico, they represent the ultimate failure of the “Peoplehood” myth.

They have the “Hardware” the skin, the hair, the lineage, but they have uploaded the “American Software.” They walk like Americans. They smile like Americans. They expect a level of service and individualism that is fundamentally at odds with the communal, expectations of the Mexican interior.

To many Mexicans, the Pocho is more “foreign” than a German tourist. He doesn’t have an uncanny valley effect. Because the German tourist isn’t supposed to be one of them. The Pocho, however, looks like the mirror but acts like the neighbor. They are proof “Shared Origin” story is not enough to bridge the gap between two different ways of being in the world. They are the strangers because they traded the “Bronze Myth” for a set of American behaviors. When they return, their face blindness is thrown back at them; they are often the most targeted for scams and the most likely to be told “you aren’t one of us.”

A Nation Searching for its Face

My conclusions it, the Mazatlán incident, the hate for Yalitza, and other examples are all symptoms of a country that is still searching for its face in a constantly evolving world

The “Mestizo Lie” was probably intended to be a shield against foreign influence, a way to tell the world that Mexico was a unified front. Instead, it has become a blindfold. By refusing to see the German-Mexican, the Afro-Mexican, the Lebanese-Mexican, and the true diversity of the Indigenous-Mexican as equal parts of the whole, the national psyche has stunted itself.

America knows more about Mexicans than Mexicans know about themselves, because America is obsessed with the reality of the demographic, whereas the Mexican government is obsessed with the propaganda of the demographic.

Until Mexico can look into its own chaotic, multi shaded mirror and stop looking for the “Cosmic Race,” it will continue to egg its own neighbors and deport its own indigenous.

This article is a narrative think piece in social observation and educated guesswork. My perspective is shaped identifying patterns and ‘glitches’ in a systems. I am not claiming to be the final word on Mexican sociology; I am pointing out where I see gaps. If you disagree with my assessment, you aren’t just allowed to say so, I’m inviting you to. Disagreement is the fuel for a better conversation.

Please don’t forget to like the article to boost it in the Substack algorithm.

Due to high demand, this article is available in both Spanish and English. Please click here for the Spanish version.

Bosch is catalan