Dia De Muertos / Day Of The Dead:

The Modern History of The Tradition

Many Mexicans and foreigners assume Día de Muertos is a time capsule event that slipped through five centuries untouched. Candles. Copal. Orange marigolds laid out like a runway. It feels primordial, and it’s supposed to.

Yet the version people recognize today: national, photogenic, and exportable was shaped in the 20th century by schools, museums, muralists, tourism officials, and brands. The ceremony families do now at home didn’t didn’t always exist in Mexico. It also didn’t exist in all of Mexico. What exist today was authored in the last 100 years.

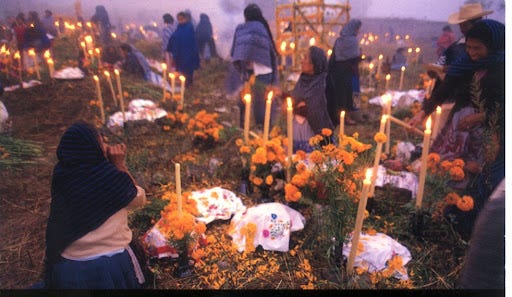

If we start with what actually existed before radio spots and mega-parades. November 1 and 2 sit on the Catholic calendar: All Saints’ and All Souls’. For centuries across New Spain and then Mexico, remembrance ran through parish life and family life. Home altars held candles, images of saints, food, and later photographs. Cemeteries had vigil and prayer. The forms were more local first. A night in Mixquic, Mexico did not look like a vigil in the Purépecha lake towns of Michoacán. Different communities also carried older ideas about death and the afterlife which included journeys to Mictlán, guardians of the underworld, into the new Catholic framework.

After the Revolution, culture stopped being only a mirror and became a lever. Mexico needed glue. Schools expanded, public art exploded, and a generation of officials and intellectuals argued that the country should see itself through “the people” and “the indigenous.” This long turn, first under José Vasconcelos at the Education Ministry in the 1920s, then more systematically in the 1930s, used classrooms, mural walls, teacher institutes, and rural programs to define what counted as “Mexican.”

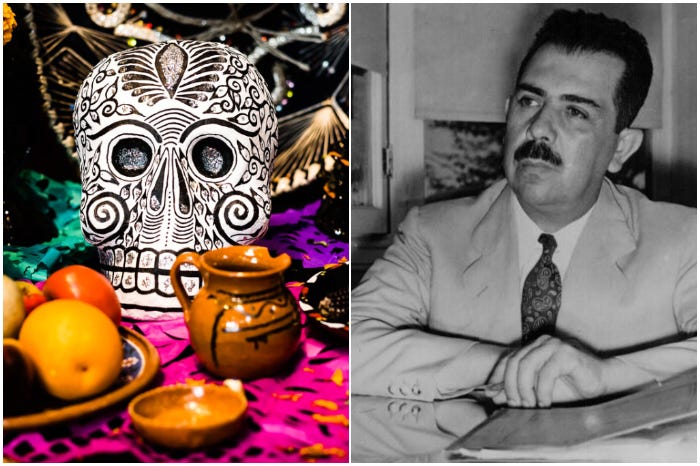

That is where President Lázaro Cárdenas matters. Between 1934 and 1940, his government doubled down on mass education and a nationalist cultural frame often grouped under indigenismo. Policy and pedagogy presented “the indigenous” as the moral center of the nation while integrating real indigenous communities into a single modern Mexico. School journals like El Maestro Rural carried the message into classrooms; curricula stressed social education; and cultural offices staged “popular” traditions in ways that sidestepped church hierarchy and highlighted pre-Hispanic continuity. The state didn’t invent remembrance, but it did standardized which pieces would be taught, staged, and celebrated as the national script.

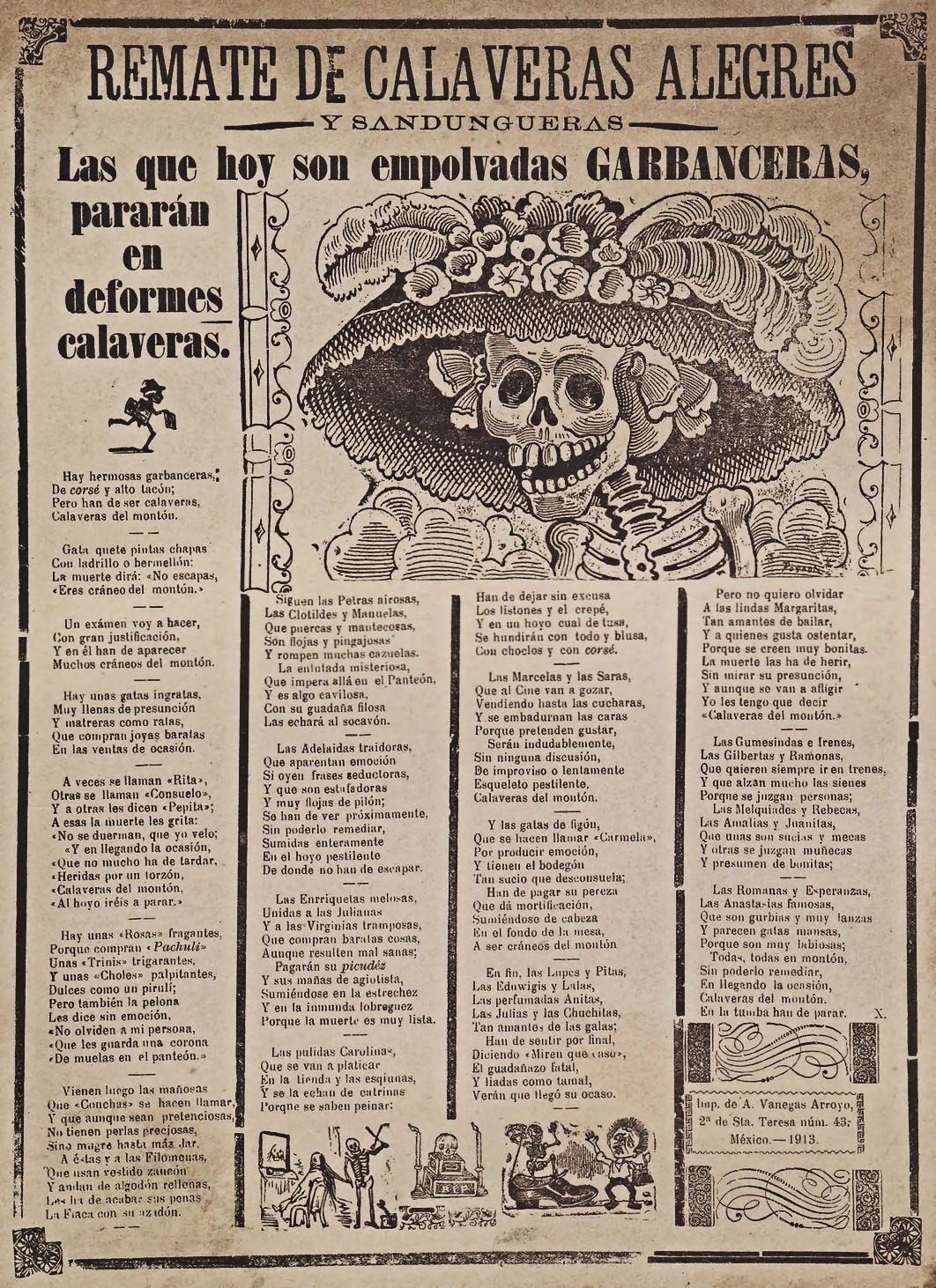

You can watch the icon making happen in real time through a single skull. La Catrina began as satire. Around 1910–1913, the printmaker José Guadalupe Posada etched an elegant skeletal lady to mock Porfirian elites aping Europe. In 1946–47, Diego Rivera lifted that figure into the center of his mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda.” With that move the skull left the newspaper broadside and entered the national pantheon. Museums and textbooks echoed the image, and a class joke morphed into the face of Mexican death. Symbols feel timeless only after institutions repeat them long enough.

By mid-century, you had two layers running at once. Families kept the slow, private rite, ofrendas at home, Mass, vigils at the cemetery. Meanwhile, the public layer grew louder and more standardized. School festivals filled late October. Cultural offices curated “traditional” altars with didactic labels.

Newspapers recycled the line that Mexicans have a special relationship with death. The materials hardened into a kit you could recognize from a distance: marigold, papel picado, skulls, candles, copal, photographs, favorite foods. The result wasn’t fake, but it was a national template laid over local practices.

The twenty-first century scaled that template. UNESCO first proclaimed the “Indigenous Festivity dedicated to the Dead” in 2003 and inscribed it on the Representative List in 2008. That language framed Muertos for the world as heritage to safeguard, and it rewarded governments and institutions for packaging the best known version for global audiences. Recognition brought money, programming, and a unified description that mirrored what Mexican schools had taught for decades.

Then cinema rewrote the streets. In 2015, the James Bond film Spectre opened with a fantasy Day of the Dead parade in the Centro Histórico, Mexico. The city made the fiction real the next year.

In October 2016, Mexico City staged its first official Día de Muertos parade. Giant skull marionettes rolled down Reforma. Floats and performers stitched together pre-Hispanic motifs, folk art, and pop imagery. The parade has returned every year since and now draws massive crowds.

Tourism logic took over from there. Airports, hotels, brand lobbies, and public plazas began competing in altar theatrics because visitors expect to see them. Mexico City reports seven-figure participation across its Muertos programming now, and the parade functions as broadcast media as much as ritual. The coverage is explicit: the event didn’t exist in this form until the Bond moment, and local officials track the economic upside along with attendance.

Hollywood amplified the export version. Pixar’s Coco (2017) offered a tender family story that distilled the national kit of marigolds, ofrendas, alebrije style creatures into a global myth about memory. Early in development, Disney’s lawyers tried to trademark “Día de los Muertos” for merchandising and backed off after public blowback, later hiring cultural consultants as the film progressed. The end product travels well and, like the Cárdenas era schoolbook, teaches a singular, emotionally satisfying narrative that millions can adopt. The good news is that more families now build home altars anywhere on earth. The cost is flattening: the farther you get from places where people sit through cold hours with candles, the easier it is to confuse a color palette with a practice.

All of this leaves a practical question: what’s “authentic” now?

The answer depends on where you stand. In Pátzcuaro’s lake towns and in Mixquic, the heart of the night is still family memory, parish rhythm, and food set out for specific people who once sat at your table. That layer does not require a parade route.

In the capital and other cities, the televised layer creates civic theater that photographs well and sells the season. It also changes every year, layering in new groups and messages; even Associated Press coverage now treats the Catrina march as a platform for many publics, from indigenous pride to LGBTQ+ collectives. The ceremony has become a stage as well as a vigil. Both uses are real. They simply serve different ends.

Put the history in one straight line.

Día de Muertos grew out of Catholic remembrance on November 1–2 and absorbed older Mesoamerican views of death. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Mexican state, culminating under Lázaro Cárdenas, selected and taught elements of that practice as national culture, with schools, murals, and cultural programs shaping a shared look and story. In the 2000s and 2010s, UNESCO recognition and mass media scaled that story; Spectre helped birth a parade; Coco exported the narrative worldwide. Families kept lighting candles at home the whole time. Institutions built the billboard around them.

So if you want to be precise when you talk about Muertos, separate the layers. The intimate rite is old and plural. The national style is modern and curated. The global brand is very recent and hungry. They overlap in the same week each year. They do not mean the same thing.

The tradition’s strength is that it can live in all three spaces without collapsing.